This series of 11 interviews was conducted in 2004 by UNSW’s Australians at War Film Archive

Transcript:

Part 1/11

00:45

I was born in England, actually. I was born a Pom I suppose you would say. My father had been British Army all his life, and he thought with the Australians right through the World War 1. So after the war, first of all he got married, as a

01:00

retired general, wives were a bit of a nuisance in the services before that. He had three children, and decided, as he retired from the army after World War 1, that he wanted to come to Australia. So I became a migrant, at the age of one. I came out from England in 1925. I was born in 1923. He settled on a sheep station in the Western District of Victoria, where I grew up,

01:31

as a youngster. I went to the local state school. When I was too old for that, ten or eleven, I went to one of the big schools down in Geelong. Geelong Grammar. At the age of thirteen, I tried for the navy, still before the war, this was, in 1936. I didn’t get in because I had flat feet. I wasn’t brave enough to tell my interviewers that my feet were flat because I hadn’t worn shoes up until then. My feet had

02:00

taken on the shape of the land on which they walked, in the bush. Anyway, I failed in that. I wanted to go into the navy because I was brought up very service-minded, by my father. Two or three years later, war broke out. I was almost finished in school, so in 1940 I joined the navy. That was what they called a special entry, matriculation, having finished my schooling. Which I think was a much better way to join

02:30

than the little kids who were going in at thirteen. They had their futures mapped out far too early for them. At any rate, I joined the navy in 1940. I went to sea only six months later, after purely naval training, not academic like the others had been doing. I went to sea in Australia’s flagship. I served right through World War 11. I stayed in the navy afterwards, because I had joined the permanent navy and had a chance to stay in. Then I served

03:00

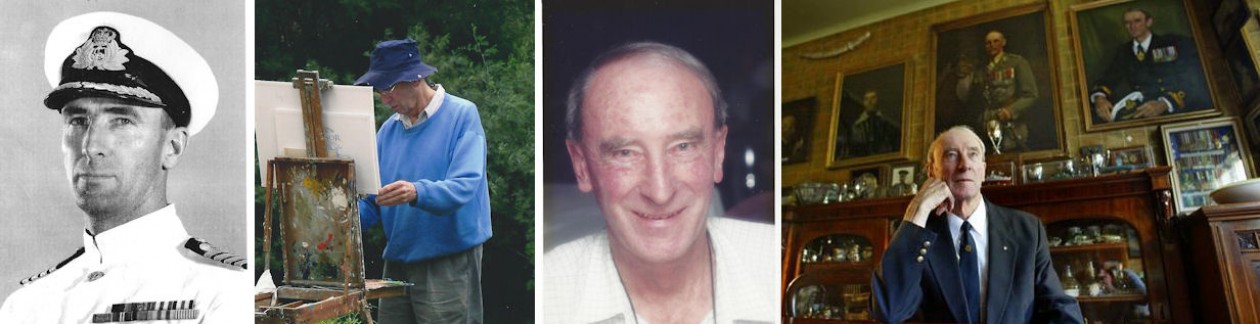

in due course in the Korean War and eventually, in a smaller way, in the Vietnam War. Finally I retired after nearly 40 years in the navy, in 1978, since which I have been enjoying my retirement and becoming an artist. That’s my life story.

Could you just give us a brief run down of the places you served in during World War 11?

World War 11? First of all, as I said,

03:30

I joined the HMAS Australia. A month or so around Sydney, New Zealand, then we took the Queen Mary, the Queen Elizabeth and Aquitania, the three biggest ships in the British Merchant Fleet, we escorted them from Sydney, right round the south of Australia, across the Indian Ocean, and they were taking troops to the Middle East. We then stayed around Aden, up and down the East Coast of Africa, Durban, East London,

04:00

Capetown, doing convoys, searching for German raiders. Interesting incidents that I will mention later. Then we hurried back to Australia when the Japs came into the war. We immediately took convoys up to New Guinea, of troops, reinforcing the very troops we had up there. We served around there, the Coral Sea, culminating in the Coral Sea Battle,

04:30

which was the first time, of course, that the Japs were beaten at sea. Left the ship not long after that, went by merchant ship over to England, where I did courses. They were still very much concerned then with the British training system. Nowadays we are much more concerned with the Americans. But then we were doing exchange service, we were doing courses and so forth, with the groups. I did courses there, for a few months. After which

05:00

there was no quick trip home, so I asked whether I could get into something smaller than the big cruiser that I had been in. And I had an interesting month or so in the Coastal Forces, in motor gunboats, on the East Coast of Great Britain, in the [English] Channel. Then I came back and rejoined the HMAS Australia. While I had been away, the Guadalcanal actions had been taking place,

05:30

and we had lost our sister ship, the Canberra, in the Battle of Savo Island. We were up around those waters for a bit. I was with the Hobart when she was torpedoed. I was in the Australia and happened to be on watch and was looking at her when she was torpedoed. But she survived. Not long after that I left the ship again and went across back to the Indian Ocean, joined a British cruiser, took passage incidentally on a

06:00

small aircraft carrier, from England to India, and joined this cruiser. We went up the Persian Gulf for actions there a bit. And gradually realised that the main task that we were going to do was back in England. We went back through the Med [Mediterranean], one or two incidents in the Med, then we worked for the Normandy landings. I was one of the few Australians probably in the Normandy landings, because we were very with the Japanese,

06:30

back here, in those days. But I happened to be the only Australian in this British cruiser and we did the landings, bombarding Sword Beach in Normandy. Then after that became a sort of a mother ship for all the small craft there, during which I spent quite a bit of time ashore with the army, helping them out, because I had been gunnery control officer of the ship, and we had become a mother ship, rather than a bombarding ship. Left the

07:01

ship again to come back. But again, passengers were a bit remote, so I had an interesting time. At that time I decided would like to see what the air force did and I joined an Australian Beaufighter Squadron in Norfolk who were attacking German shipping, off the Dutch Coast. It was interesting to see the other side of life. What is was like to be shot at by a ship rather than being in the ship shooting at the aeroplane.

07:30

When I finished that I got passage in another naval ship back through the Med to Ceylon where I joined an Australian destroyer, the Norman. I served in her up and down the Burmese Coast, doing the final Arrakan advance down the coast of Burma. With Bill Slim [General Sir William Slim], the general, doing his famous victory procedure down the coast.

08:00

When we’d successfully done that, we rushed back around the south of Australia, rejoined other N Class in Sydney, and joined the British Pacific Fleet, went up north with them, operated with the British aircraft carriers who were operating with the American carriers, in an enormous collection of ships by then. We did the Okinawa landings, the Sakashima landings. We were preparing to do the landings

08:30

in Japan, which was a worry for us all, because we realised how fanatical the Japanese were. And fortunately, I think still, the atom bombs put an end to the war before the millions that would have been killed in the final struggle. We actually were off the coast of Japan and saw the sunset on the night of what we, the next morning, found out was the atom bomb on Hiroshima. Which was quite an interesting

09:00

experience. And that was the end of the war. We then had all the post-war business of running down and returning to Australia. I stayed in the navy then, and it was only a few years later we found ourselves starting the Korean War.

You were also in BCOF [British Commonwealth Occupation Force]?

Yes, we spent two or three trips up in BCOF, immediately after the

09:30

war. In fact we took, on the frigate I was then in, the Murchison, we escorted the main BCOF contingent from Morotai up to Japan. And having at that particular time, having to tow an LST [Landing Ship Tank] all the way, which broke down right at the beginning. That was quite a long tow we had to do, to get them there. So BCOF, we operated all around Japan, in the Occupational Forces. In fact,

10:00

had done one trip up there in the Battan, in 1949, and were going back for the second trip in 1950, and left Hong Kong the day the Korean War broke out. So we were in Korea, fighting the Korean war, three days later. We were right at the beginning. The first six months of that war were the most active, those six months that we had. And I came back and had all sorts of peacetime activities, until finally

10:30

the Vietnam War, when it was on, I was commanding the big fleet tanker, the Supply. We weren’t very war-like, we didn’t go in and fire guns or anything, but we did a certain amount of logistic support for the ships that were taking troops in, or were bombarding. So I played roles in the three wars, until finally I had a few more peacetime jobs and then I retired quietly in 1978.

11:04

Let’s go back to the beginning now, and we’ll talk in a lot more detail. Firstly, I understand your father was awarded the Victoria Cross?

That came way back. People, when they hear he had a Victoria Cross, they say, “Oh, World War 11?” “No.” “World War 1?” “No.” “Boer War?” And I say, “No.” They “Before that?” And I say, “Yes, the Khartoum Expedition

11:30

of 1898.” With Kitchener relieving Khartoum, in the Battle of Omdurman, my father was one of four Victoria Crosses. Virtually won on horseback with a sword. I think he was waving a pistol around, too. So that’s fun to always have that in the family. I still have the Victoria Cross hanging proudly in my dining room. Because he was a soldier and he spent his whole life

12:00

in the British Cavalry, until he became more of an Infantryman in World War 11. I was sort of service-minded from my upbringing. He had left the army before I was born, so I didn’t actually see him being a soldier. Although he was often back in his uniform for Anzac Day parades in Western Victoria. Opening war memorials. There’s one down in Portland I always like to have a look at. Opened by, and dedicated

12:30

by, Major General Sir Neville Smyth VC. So I’ve always been rather proud of that.

So you were born in 1923, how old was your father then?

He must have been about 55. As I said earlier, he retired from the army and then got married. It must have been quiet a shock for my mother, who was twenty years younger than him, to find herself marrying a knight and a general and a VC winner.

13:00

Normally you’d marry someone who was in their 20s, not someone who was in their 50s.

So he was knighted as well?

Yes, he was a knight. At the end of World War 1. World War 1 I would like to mention. He wasn’t at the Anzac landings, he was then actually back in Khartoum as the Military Governor of Sudan. Which was a funny sort of job. But it was where he won his VC

13:30

seventeen years earlier. The General Bridges [Major General William Throsby Bridges, KCB, CMG], who you may remember was the head of the Australian forces at Gallipoli. He was killed early in May, and one of the brigadiers was promoted to take his place, as the divisional commander, and they didn’t want to promote the colonel under him up to brigadier, apparently, he was too junior at the time, and they looked

14:00

around quickly for someone to take over, and there were various other British officers with the Australian forces then, and they grabbed my father from Khartoum, and they rushed him up, at very short notice, and he took over the First Brigade of the Australians on Gallipoli. Where he had a very active time, including, I think, the only battle we really won in Gallipoli, was the Battle of Lone Pine, and he was the commander of

14:30

the brigade that fought the Battle of Lone Pine. I’ve always been rather proud of that. Then he stayed with the Australians. He went to France with them, after the evacuation of Gallipoli. In 1916 he was promoted from brigadier general to major general, and he then took over the 2nd Division, right through Posieres, Passchendaele, all the nasty battles on the French

15:00

and Belgium area. By halfway through that, he was given the Commander of the Order of the Bath, and he was given the French Partiguere [parte le guerre] [Croix de Guerre] and the Belgian decoration. At the end of the war he was knighted. He left the Australian forces early in 1918, when they finally Australianised, completely, the commands. He was the last

15:30

of the British officers to lead. I think he was…. Well, I like to think he was, the most popular of the British officers amongst the Aussies. Partly because he had a VC and they knew that he was a fighting general, and not of these generals who hid behind the lines and ordered everybody in to be slaughtered. And he was so fond of the people he served with. As I say, there was no question in his mind that when he retired, a year or so after the war, he had been

16:00

writing to his Australian friends and he finally came out. He came out first by himself, had a look around…. I know your head office is in Orange, and the first place he decided to settle was Orange. I found that out when I went there, not long after World War 11. I was the ADC [Aide de Camp] to the Governor-General and I visited Orange, and the very first person I met, he said, “I knew your father. He came here in 1924 and he wanted to settle here.”

16:30

He decided, in the end, to settle in Victoria, instead. At any rate he decided to settle in Victoria, then he came back and got us and brought us out in 1925.

Now the various things that you know about your father, is that from him telling you? Or did you find out later?

I think I found it out later. Like all those World War 1 people, he was pretty reticent. He would talk quite a lot, naturally, about

17:00

experiences. But they were never the wartime experiences, they were more, “I remember the time I was in Egypt when I was stung by a camel scorpion, and I very nearly died. But I dealt with it. I had lain down in my stretcher and it had bitten me on the temple. So I picked up my cut-throat razor and I slashed my temple until it poured with blood, and I saved my life that way.” He would tell you those sort of stories, but he wouldn’t mention that the day before he had been

17:30

slaughtering Dervishes in the final battle to track down the Khalifah Abdallah, the successor to the Mardhir, and that sort of thing. And yes, I’ve read a lot about him. There’s a lot of books where he gets mentioned, the official histories of the war. The Australian official histories. I’ve never been able to get his biography written. One person was very keen to do it, worked on it for

18:00

ten years, got through almost to the beginning of World War 1…. After all, he had started his actions, his front line service had been in 1890, up in the North West frontier of India. So there was quiet a lot before the World War 1 time came. And the chap who was writing it finally died, unfortunately. I’ve still got his prepared work, but I still haven’t found another author yet, to do the rest of it.

18:30

I’ve got one or two in mind, still.

Can you tell me about your early childhood in Australia? What were your first memories?

It was a delightful life, on a sheep station in Western Victoria. Riding my little Shetland pony, with my sister, the three miles to the little country state school, every morning. Before that, I suppose, we first of all had a governess, because

19:00

there was no state school, at that stage, within cooee [Australian call, large distance] of us. I had an elder brother and an elder sister, and the governess would try to look after us, and keep us under control, which was impossible. We had a delightful life in the country. I had my own dog. I’d go wandering around with my dog and my air rifle, first, and then later on a .22 rifle, then finally four ten shotgun, shooting rabbits. I actually shot

19:30

a fox one day, which was very exciting. All at the age of about eight or ten. And lots of trips with…. The overseer on our sheep station was an ex-English fellow, but a great hunter. He loved going hunting kangaroos and going fishing. He taught me all the bush boys sort of activities. As I say, I seldom wore shoes. Even riding to school you didn’t need shoes, because your bare feet were in the stirrups of the

20:01

saddle. So I had a delightful life there. Two years at the little state school, where there were only ten or eleven pupils only. I think the second year I claimed to be the dux of the school, but as there were only twelve pupils, it wasn’t terribly clever of me. Then I had to put on shoes and go to school down in the big city. It was a wonderful upbringing. My father, having been a cavalry man,

20:31

everything was done with horses. He did all the ploughing, with a horse drawn plough. He even had a paddock which he called the polo paddock. I don’t think he ever actually played polo on it, but he had been a polo enthusiast in the army. He had been a big game shooter. We had a house full of stuffed tiger skins and lion skins. As you walked into the hall, there were three lion skins and one tiger skin,

21:00

with just the head stuffed, and the rest of the skin lying on the floor, and you looked into these gaping mouths and flashing eyes as you walked into the hall. Those have long since rotted away, but that was the sort of upbringing I had. The next big-game hunter-soldier, who was to me a sort of an automatic hero for a very small boy to live up to.

How big was your sheep station and where was it?

21:30

It was a place called Balmoral, north of Hamilton, south of Horsham. The Western District. It had been a very big station, I suppose about twenty or thirty thousand acres. It was taken over, after World War 1, for the Closer Settlement of returned men. As a matter of fact, Indian army officers were, for some reason, allocated to that particular area. Not Indians, but British people who’d been in the Indian army. So the

22:00

main homestead was reduced to a thousand acres, and lots of other one thousand acre blocks were set up and houses were built on them. And all these Indian army officers were settled in there. The people who had owned the main homestead, Congul as it was called, were so disgusted at being reduced, compulsorily to a thousand acres that they sold the place, to my father, who had found it for sale when he came out. So we started off

22:30

with only a thousand acres. The Indian army officers were partly not on really…. blocks of land that were big enough. Secondly they didn’t know very much about running a sheep station. They hardly knew what a sheep was. So by the time that the next war came along, only fifteen years later, they’d all failed and moved to the city and disappeared.

23:00

All except one family, I think. And my father, who had gradually brought up two or three of the other ones…. I think we finished with about four or five thousand acres, running merino sheep. Lovely rolling red gum country. One of the nicest parts of Victoria. It’s not flat and dull, or bush, it’s just big red gum spread park-like, over nice rolling hills with beautiful white merino sheep. My wife

23:30

never forgave me for not going back to the farm after World War 11, when I could have gone…. My father had died early in World War 11, but I decided to stay in the navy. I often regret it myself to a certain extent, that I didn’t go back. My mother had kept the farm going during World War 11, for me or my brother. We both said, “No.” I said I wanted to stay in the navy. My brother had been invalided out of the Welsh Guards after being wounded in Italy during the war,

24:00

and he had become a diplomat. And he said, “No, I want to be a diplomat.” So the place was sold and we rather regretted it, ever since.

Now your father being an army man, was he a very strict father?

I don’t think so. No, he didn’t really know very much about children, mind you. I think he left the upbringing of us to our dear mother, who was a good mother for us.

24:30

He was a bit distant, I would say. I didn’t quite call him ‘sir’ but it was almost in those days when you did. He was always ‘Father’ to me. I’ve still got a letter somewhere. At school, everybody else had been talking about their Dad, and I had been talking about my father, so I finally wrote to him and said, “Would it be all right if I called you ‘Dad’, Father?” And Father wrote back saying, “Yes son, you are quite welcome to call me ‘Dad’. Actually ‘Dad’ is interesting. It comes from the original Welsh word ‘Tad’,

25:01

T-A-D, which was first…” And he went on and on in his letter about this. I don’t think I ever get around to calling him ‘Dad’ because I respected him, enormously.

Now you mentioned before that you used to hunt for rabbits. It brings to mind the very tough years of the Depression.

25:30

You would have been around about seven or eight when the Depression started….

Yes, I don’t really remember the Depression, as such. I mean, obviously, it was on. I remember the tramps, who seemed to be more numerous then. They’d come up and ask for something… At its basic, just a meal, but often asking if they could do a bit of work, and we’d try to give them a job as a hand on the place. We only had about one person working on the place

26:00

perhaps two. My father did most of the hard work riding around the bush, pointing his swagger stick at things to be done, to the employees, the two men. The fact that he was able to send us all to boarding school surprises me, in retrospect, because I don’t think he ever really made very much money on that farm. He wasn’t a farmer at heart.

26:31

He was fairly impractical. He had a bit of an army pension, not very much in those days. I think even the VC gave him a pension of about two pounds a year, which seemed absolutely ridiculous. But it had been set up in 1856, when the VC was invented, and it had never changed. Two pounds then would have been probably quiet generous, but he had something else, too. And it wasn’t until he died, and that pension

27:00

disappeared with him, in 1940, that my mother had to make the farm run. And she ran it during the war. All of the men of the farm went off to the war. She was running it single-handedly, with the aid of one local dwarf, who was a charming little fellow, but he was only about three foot high. He couldn’t even reach up to milk the cows. My mother had to milk the cows and carry the milk buckets

27:30

back to the dairy. And later on, he was added to by an Italian prisoners of war, who had been a circus trapeze artist in his peacetime and he was delighted to have been captured. He didn’t want to fight in the war. He was a very pleasant fellow. I like to think that perhaps he settled in Australia after the war.

Your mother sounds like an extraordinary woman, can you tell us a bit about her?

Well, she was, I think,

28:00

extraordinary, and anybody who remembers her, particularly the sight of her, there were one or two books written a few years ago…. Somebody who had gone there as a Land Girl during the war, at one stage, to help out, knew that she was going to meet Lady Smyth, who she thought was going to be a frightening sort of person. The person she met was wearing very old clothes and

28:32

a belt full of knife and shearing sheers and a woollen cap pulled down over her head, riding a horse, saying, “What are you? Oh, you’re the new girl. Straight down to the dairy and milk the cows because I haven’t got time to do it.” And she really did hold the place together. After the war, when she finally sold it, she retired to Portland, it was still well known in the area for being the

29:00

sort of ‘can do’ person she was. I’ve always been rather proud of both my parents, for different reasons, in that regard.

She was obviously fairly tough, what was her upbringing and background?

She was a Welsh woman. She was (UNCLEAR). She used to speak Welsh if she had to. I never did.

29:30

I have been to Wales and met her cousins. Her father was a baronet. Sir Osmond Williams, head of Merry Oldham, the northern Welsh county, I suppose you would call it. She had been brought up very much in the Welsh country. So it fitted her somehow.

30:00

I think she probably proposed to my father. He never having very much to do with woman in the army, was attracted to her and they had a lovely story. He finally went to stay with the Lord and Attendant of Mary Onan Shirley, Sir Osmond Williams, because he was admiring the daughter of the house. They went for a long walk on the….

30:30

beaches of the Perrin Dydruf [?], area. And when they returned, my mother was all alone and somewhere half a mile behind my future father was trudging along. My mother said, “Well, it’s all fixed. We’re going to get married.” And that was apparently the announcement. My future father sort of ambled in and said, “Yes, yes, we’re going to get married.” Silly

31:00

stories one remembers from one’s youth.

Were they religious, your parents?

They were good Church of England goers. I think, actually, my mother was probably Chuppel. Welsh people were Chuppel. I’m not quite sure what it is. It’s rather like the Presbyterians, I think. And I know when we’ve been in

31:30

Wales, it’s Chuppel they go to, very religiously. He was a good Christian, my father, there’s no doubt about that. I have a delightful… At his funeral, the Bishop of Ballarat, I have his sermon, his address. Eulogy. I know that we always went to the local church and so forth. But I wouldn’t

32:00

say they were more than just good solid Christians. The sort of persons I think most of my friends are. They don’t go overboard, but they do accept that there is probably some higher authority up there, who somehow put us on this Earth.

So they weren’t zealots, but they were believers and practised.

The local church, at Balmoral, I’ve been back there a few times….

32:32

When my father died, we presented a rather nice carved wedge-tailed eagle as the lectern, from which the lessons are read. There’s a nice brass plate commemorating the fact that he worshipped in that church, and he’s buried in the little Balmoral cemetery. Actually, Bruce Ruxton [long-time President of the Returned and Services League] a few years ago was up there,

33:00

and I knew Bruce quite well, and he knew my father had been a VC winner, and he went to see my father’s grave, in the Balmoral cemetery and it was in disrepair and he was horrified. He came back and he made quite sure that it was arranged from then on that every VC grave in Victoria would be properly looked after, henceforth, by the RSL [Returned and Services League]. So that was something. We were a bit ashamed. We had been up and cleaned it up a few years earlier, then we’d forgotten about it,

33:31

and good old Bruce Ruxton fixed it for us, so now it’s being looked after.

You mentioned that you didn’t remember much about the Depression, tell me about that time in

34:00

general, though…. What sort of food did you eat? And you went to the local state school, you must have seen other kids that weren’t doing so well?

I don’t remember them as not doing well. Every house had its little vegetable garden, where we grew most of our own vegetables. We ate mutton, dreadful mutton.

34:30

When the Marino sheep ceased to produce very nice fleeces, you tended to put them in a paddock and called them, “The Killers.” You’d kill a sheep, there was no refrigeration, so it would hang in the meat house until it started to smell a bit, then you would kill another sheep, and eat that. Mutton is not exactly like the lamb you have today. It was a bit tough, but I didn’t think of that. No doubt, we also occasionally….

35:00

I don’t think we ever killed…. We only had dairy cows, we didn’t have cattle as such. So we probably occasionally we probably got a steak or something like that. I can’t remember that. I think mutton was the only meat I understood. But you can do a lot of things with mutton. You can grind it up by hand in a mince-meat maker, and finish up with the equivalent of your modern….

35:30

hamburgers. I don’t think we called them hamburgers, then. I don’t know why they called them hamburgers. They haven’t got ham in them, they’ve got beef in them. We ate what the ground and the land could produce for us. I think all the other families were much the same. We joined with them for various things.

36:00

We drank home-made barley water or lemonade. We had lemons. We had an orchard with all the fruit in it, at the right time of the year. I really don’t remember the Depression, except for extra tramps, and wondering why there seemed to be more of them. But you know, at the age of seven or eight, you can’t really remember much.

36:30

I think the earliest memory that I can possibly…. I’m only remembering having remembered, is going down to Portland in the summer on the train for a holiday. I think I was five, but I think I am probably remembering, without really remembering.

Did you eat rabbits?

Oh yes, rabbits were very good. There was no myxomatosis or anything nasty like that in those days. I made pocket money

37:02

by selling the skins. Some people, of course, sold the actual rabbit. We sold the skins. The skins brought in a few cents each or something, which was quite good. I used to have a couple of ferrets. I would go out with the ferrets and put them in the burrows, the warrens, there were quite a lot of rabbits around still. We spent a lot of time

37:30

trying to deal with rabbits in one way or another. There was some machine that used to pump nasty smoke. We used to drag this machine along with the horse, there was a fire going in it, and somehow we pumped into the warrens. But for those who had to fill in, close all the outlets, in the hope that they would all be exterminated inside, which I suppose it did.

38:02

Sometimes I used nets. But mainly I used to stand there with my little four ten shotgun, and waited for the rabbits to bolt out, and I shot them. I was a very good shot in those days. I was never as good when I graduated to a twelve bore [twelve gauge] shotgun. I was never as accurate as I was with my funny little, single barrel, four ten shotgun.

Did you graduate from your Shetland pony?

38:31

Not really. Because once I left the state school and went down to the big school…. There were other ponies. There was a bigger pony that I rode occasionally, but I really haven’t ridden since them. In 1973, thirty years ago, I was asked to lead the Anzac march, here in Melbourne. I was still in the navy,

39:00

and I thought it would be rather fun, if I got into a naval officer’s riding kit, which did still exist in the textbooks. Which was black gaiters and white normal sort of dress-up, buttons, tie, medals and everything, in a monkey jacket. But down below, white britches and black gaiters. And I knew the Chief Commissioner of Police fairly well and I said, “Can I borrow one of your horses and actually ride it,

39:30

as the leader of the Anzac march?” He said, “That’s quite a good idea, I think I will find you one.” Then I’m afraid I went chicken. I thought, “Now I’m still in the navy and the navy is probably going to say I shouldn’t be behaving like that, and anyway, I might fall off and disgrace the navy.” I hadn’t ridden a horse…. So I didn’t do it. And I even thought of doing it again three years ago when they once again asked me to lead the march. And I thought, “No, I’m now very much retired, I’m nearly eighty and I don’t think I should be trying to ride a horse.”

40:00

And I didn’t.

Actually I will pause there….

Part 2/11

00:39

I just want to ask a little bit more about the area in which you were growing up, and the school that you went to, was there a mixture of races and religions at all?

I wouldn’t know the religions. I imagine there might have been an odd Roman Catholic. There were certainly no other races.

01:00

We didn’t have any Aborigines near there. They were down towards Portland more, where they still are. No, they all seemed to me to be perfectly the same as me. And their fathers were all Major Norton, or Captain Wells. They were all ex-army people, so to me I suppose I assumed everybody was ex-army. And although all of those were ex-Indian army,

01:31

Victoria at the time was still full of ex-soldiers. Those that had survived. After all out of one and a half million Victorians in World War 1, ninety thousand went to the war, which is an enormous percentage. Of those, one in five were killed. Nineteen thousand were killed, out of eighty nine thousand, which is a frightening proportion. But

02:00

nonetheless, every family…. had somebody coming back from the war or had somebody not coming back from the war. The place was still being run by the old father or the wife or something like that. That’s why all these war memorials were built. Every little hamlet, every village, had its own war memorial. In those days, they were still being built. As I say, I remember my father dedicating the new

02:30

Portland Memorial. There’s a little one in Balmoral that I remember we used to go to, every Anzac Day. It is my sort of memory that it was a post-war country, or state, that one was living in. And as far as I was concerned, even more so because my father had had all those other wars before. He lived in a world of war I suppose. It wasn’t that long after that, that sure enough, we were in the next one, too.

03:04

The era sounds interesting, or unusual, in that…. Would you say that most of the kids at your school were from British soldiers?

Yes, at my little school that was true. Going a little further away, though, outside the Koonongwootong Closer Settlement area, there were several people who

03:30

had fought with my father. Good genuine Australians. A chap called Gus Oakes, a chap called Bill Winter Cooke, who had been with my father with my father. And that might have led him to Balmoral. He probably knew they were living there, and tracked them down when he came back out in 1924. They were all great people. At the time, they just seemed friends of my father. I have since learnt of their own…. Gus Oakes

04:01

had a Military Cross. I didn’t know much about medals as a boy, I just thought that everybody had medals. But he had a Military Cross, which he got fighting under my father in France. Bill Winter Cooke, his son’s still running Murndal, which was about thirty miles away from us, he was the one that brought back…. Not the Lone Pine,

04:31

that’s a different story. You probably heard about how the lone pine was brought back? The lone pine itself was sitting on top of a little mountain. A single lone pine. A lonesome pine, they called it originally. And my father, the night before the battle, sketched it and that’s the only known picture of the original known pine. But after the battle, it had been blown to bits, by gunfire.

05:00

And somebody picked up a pine cone from it, sent it home to his aunt in Australia, who some years later remembered it was sitting on the mantle piece, gave it to some experts who were able to grow a lone pine from it. And that’s the Lone Pine at the Shrine of Remembrance here in Melbourne. There are now lots of grandsons of lone pine. I planted one down at one of the schools in Melbourne, only two or three years ago.

05:31

The headmaster knew I was the son of the general who fought the Lone Pine Battle, and we planted this lone pine, which has now grown up. Bill Winter Cooke, who I mentioned, he at Gallipoli picked up some acorns from the Gallipoli oaks. They’re not really oak trees as you and I know, like the English oaks. They’re very spiny.

06:01

They’re more like a holly. In fact, I call them a Gallipoli Holly Oak. He brought a handful of them home, and he planted them in the grounds of Murndal, one little Gallipoli oak. And the other one in the grounds of Geelong Grammar School, because he had been at Geelong Grammar. And recently

06:30

because my wife’s father had been second in command of the submarine AE2, which forced the Dardanelles, on the original Anzac Day…. I was in charge of the grounds around the shrine here where we’ve got about four hundred trees. About two hundred of them are dedicated to a particular ship or unit or squadron. We didn’t have the AE2 commemorated there,

07:00

so I was able to get one of the Gallipoli oaks, which had been again the grandson of the original one brought back, at Murndal and at Geelong Grammar, and I planted that and it’s now taller than me. I do digress rather, don’t I?

That’s okay. I wonder what the Customs Department has to say about all these pine cones and acorns

07:30

coming back into the country…

At the time they were welcome. I should think now they would get burnt.

Given this background, the people and the area generally, and the returned soldiers, and in particular the British soldiers, I’m interested to know both through informally and formally at school, what sort of things did

08:00

you learn about previous wars? Particularly World War 1? What were you told and what did you learn, about what went on?

I don’t think school ever did anything other than mention it in passing. The history we learned at both the state school and later on in the bigger school, was Australian history, but all explorers. Nobody seemed to be anything except an

08:30

explorer in Australian history, as far as we were concerned. My brother was much more intelligent. He was a very good student. He studied Ancient History and European History and Roman History, and he was an historical buff, and he was the dux of Geelong Grammar. My headmaster at the time, only a few years ago before he died, once said to me “Dacre, I do think that your brother Oz [Osmond] was

09:00

the most brilliant mind that ever went through my school in the thirty years I was headmaster.” So my brother was an historian, and he would be able to answer your question much better, if he were still alive. No, I think the war was still so close behind, it wasn’t history. It was…. .what is the difference between history and recent events. But you can probably see what I mean. Now,

09:30

it’s history. My own war is now history, because it’s a long time ago. But I’m talking then in the days of only ten years after the war. You certainly think of history as something ten years ago.

Well, informally then. Did any of the adults talk to you about your own experiences? Did you have a picture of what war was like?

No, I don’t think so. I don’t think any of them really

10:00

liked talking about it. They had a much nastier war…. Well, I had a very nice war. I was in the navy. I didn’t have to put up with any of the things the army had to put up with. The sands of the desert, or the mud of the trenches, or the mosquitoes and leeches of the tropical forests. I avoided all that. But I think that First [World] War , the trench warfare, the more one reads about it, the more horrific it must have been.

10:31

I’m just reading a little book now, a fairly recent one, all little half page extracts of people actually talking, rather like what you’re doing to me now, they extracted all this from people, of the First War. And some of the descriptions, in just a paragraph or two, wading waist deep. Not through mud, but through mud and decaying bodies.

11:00

Well, that’s not the sort of thing that little boys would be told about by the people who put up with it.

Were you told of the British Empire, though, and….

Oh, very much. My father, of course, was terribly sort of British Empire minded. He had come to Australia, but Britain was still his home. He never went back. I don’t think my mother went back for, oh, thirty years.

11:31

She went back, actually, for the centenary of the Victoria Cross in 1956, the early ’50s. They remembered that she was the widow of a VC. That was her first return. So they had taken on Australia, embraced Australia and become good Australians, but they were still terribly British at heart. I’m accused, still, of talking like an

12:00

Englishman, because I was brought up, I suppose, listening to them with an English accent. I don’t think I’m terribly English, but you would know better than me. I can’t hear myself.

You mentioned that your father was a large figure in your life, He loomed large. He was a hero to you.

12:31

You must have known something of his exploits when you were young?

Oh, at some stage I realised that having a VC was something a bit special. All the other medals he had were interesting when he put them on. I can’t remember a moment that I realised he was a hero. Or realised that there was any difference between him or anyone else.

13:03

He normally didn’t go around wearing uniform. Rather like the description of my mother’s clothes. His were all terribly old. If he tried to do the ploughing with the horse, he didn’t exactly look like a soldier hero.

But he sounds interesting in that he did form some kind of bond with Australia, and decided to turn his back on

13:30

Britain and decided to come over here. Do you have any inkling why he might have done that?

I do remember that to a certain extent…. I have got writings by him somewhere, I think, perhaps when he was writing to his friends over here, saying to them, “I would like to come out because I don’t see the future for England.” In those days, 1920, ’23, he could see England

14:01

going to the dogs. No, he was typical British…. not upper-class, but successful middle-class I suppose. And felt that there was more…. And he was an adventurous fellow, having fought around the world. Not only fought, but did peacetime soldiering. The challenge of coming to Australia, where

14:30

he had so much admired these fellows that fought under him. He did like an Aussie, and they liked him. And they got along terribly well together. And after the war it seemed almost automatic that he would want to come out.

At the school you were at, were they strong believers in the Empire

15:00

as well? Do you remember such things as Empire Day?

Oh yes. We used to, every morning, we would, all ten or twelve of us, we would line up and we would hoist the flag. We would salute it. I don’t think we sang anything particularly, but we’d have our little ceremony.

No God Save The King?

Oh yes, but not every day. We might have, I can’t remember. I do remember that we had

15:32

a sort of routine during that morning assembly, where you had to each say…The first thing you had to do there, there was a roll call. And the first few days I couldn’t understand…. They were saying, “Dacre Smyth?” And I was saying, “Presermiss.” [Present, miss] And I had no idea what ‘Presermiss’ meant. It was a sort of a new word to me, but I went on saying ‘Presermiss’ until finally,

16:00

one of the others spoke it a bit more clearly and I realised he was saying, “Present, miss” to the schoolteacher. Then we were asked if we had anything interesting to report. And there’s a chap who I’ve only recently re-met, who was Major Norton’s youngest son, Mark Norton. A very nice fellow. I’ve seen a bit of him. And this particular morning, I said, “This morning as I was coming to school, I saw a fox.”

16:31

And everyone said, “Ooohh, that’s a bit special.” And my sister said, “This morning when I was coming to school, I saw two foxes.” And I rather looked at her, and I didn’t think she really had seen…. I had seen one. At any rate it came to Mark Norton’s turn, and he had been looking at us with envy, and he said, “This morning, as I was coming to school, I saw a lion.” It’s a silly thing that you remember.

17:02

What sort of things did you do with other kids, or by yourself, what sort of things did you do for fun? At the school or at home?

At home we were very much just the three of us. We got on well together. I don’t remember having any real fights. We would do a lot of riding around the place. We had a dam. My father had got a little boat built for us,

17:30

just big enough for the three of us to row around the near dam. The far dam had fish in it, so we used to go fishing there. The near dam we didn’t think had fish, until I put a line in, one day, and went back the next morning and pulled it in and found an enormous tench on it. The far dam had English perch, but the tench was a big slimy fish and had obviously been in the dam all that time and we hadn’t known. So we caught a few more of that.

Is that a native or…

18:00

No, English tench brought out by somebody. And English perch of course, the red fin, it was imported, too. The dams wouldn’t have had any natives. The creeks and the rivers had natives, but again, mainly the English perch seemed to have taken over. The Greenalge River we did a lot of fishing in. We went shooting. Jack Whistler, our overseer, ran a lot of bees. And I used to

18:30

go with him and we’d move the apiary from one spot to another. We’d do all the getting of the honey out of the combs. The extractors. You’d whirl it around. It was sliced off the outer covering of beeswax and then you’d whirl it around so it all flung

19:00

out into a sort of forty four gallon drum, extractor thing. And then you’d take it off. So there were all sorts of country things like that that we used to do. We used to go on picnics up into the Grampians. I remember one Christmas…We normally had a fairly traditional Christmas at home, but for one reason or another we went on a picnic to somewhere in the Grampians.

19:32

We were almost attacked by what we thought were wild cattle, while we were having the picnic. But I don’t think they were really wild and I don’t think they ever really attacked us. But those are the sort of little memories you have. Very much a country upbringing, and finding your own fun on your own farm, with all sorts of…. Every tree on the home paddock, my brother, particularly, gave it a name. There was one which was the Elephant Tree, because it looked rather like

20:00

an elephant’s foot. And we had an elephant foot in the house, which my father had shot in Africa at some stage. Then we found somewhere else, at some stage, that the original settlers of the house, two of them, the two Mailer brothers, one of them had gone out to the far paddock and spent a couple of nights out there, looking after the sheep. While he was away, the other

20:30

brother cut down a tree, it fell the wrong way, it pinned him to the ground, he couldn’t get out. He tried to chop his way out, it was an enormous tree, and when his brother came back he found him dead there, with his face eaten off by wild dogs. So we found a place that we thought was his grave, so we dug it up, but he wasn’t there. These were the sort of excitements and stories…The homestead that we were living in

21:00

wasn’t terribly old, it had been built about 1900. So it was only then thirty years old. But the old homestead had been built in the 1840s, and it still there today. It was a lovely old homestead. The overseer used to live in it. So it, itself, was something to explore. And then of course there was the shearing time and the cutting of the crops in the summer. Once we

21:30

went away to school, we still…. Whenever we came home on holidays we were flat-out all the time, doing the farm work. I remember all the cutting of the crops, particularly when the war came. The bush fires that we used to have to fight in the summer and the dwindling number of men to do the work, whether it was cutting the crops or putting out the scrub fires or the grass fires. It was a country life that

22:01

one remembers, more and more, as one gets older, really, as the greatest way to be brought up.

How did it happen that you went to Geelong Grammar?

Well, Commonwealth State School Number 4462, only took you through to age eleven….

22:31

fifth grade or sixth grade, I think, whatever they called it in those days. So we had to go somewhere. The nearest high school was in Hamilton, forty miles away, so I couldn’t of commuted to that, so I had to go to a boarding school. My brother had gone off two years earlier. And of course the nearest boarding schools were in Geelong. Geelong College and Geelong Grammar. And Geelong Grammar, particularly, seemed to be

23:00

the one that nearly all the Western District people…. A lot of the locals just finished. My schoolmates at Kongul [?] State School, I don’t think any of them went on to high school. They finished and they went on the farm, where if they failed they finished up in the city somewhere. But those that were going to go and try to get an education had to go to the big city and the nearest big city was Geelong. Geelong Grammar, just out of Geelong was more countrified than

23:30

Geelong College, right in it, so I suppose that was why my father and mother chose that for us.

So how did you find it? It must have been a bit of a shock for you to go from a school of twelve kids to a school of several hundred?

I started in a prep school right in Geelong called Bostock House.

24:00

And it wasn’t as big as the big school. It had, probably, twenty boarders, and sixty or eighty day boarders. And it was just filling in the two years between…. I went there at the age of ten and did two years, I think. I left at twelve and went up to the junior school

24:30

of the big school in Corio. It was a change, yes, certainly, to find yourself miles from home. I don’t remember being particularly homesick, somehow. And the other kids weren’t too bad. I never suffered at school from any bullying, or took part in any bullying. For some reason it might have been going on. From what one hears, it’s still goes on.

25:00

But I was lucky, I always enjoyed school. I got along well with most of the others. There were some people you didn’t like and some people you did like. That’s life anywhere, isn’t it? So I was very happy there. Very shortly after going there we had our annual athletics and I found myself the under-twelve athletics champion, at the age of ten. Well, that put me in a good spot, so nobody was going to pick on me after that. I even set the

25:30

under-twelve long jump record of thirteen feet and two inches. I often wonder whether it still exists, that record. I don’t think it does, but it’s nice to think it might.

So did you make a lot of friends?

Not really, no. I was friendly with everybody.

26:00

I think I’ve been right through my life, not close friends with people, in the navy. But in school, the friends I made I then never saw again. Most of them were killed in the war, I think. I went off with the navy and it wasn’t until I came back here to Melbourne, for my final posting, really, that I started catching up with a few of them, again. So none of them are close friends. I just like

26:30

to think that I’ve got lots and lots of friends. It varies with the individual I suppose. Some people need two or three very close friends. I’ve never had them, so I’ve never needed them and never missed them.

Did you have any contact with girls at all?

I remember feeling rather frustrated at school, for obvious reasons.

27:01

As one grew up and became a teenager at Geelong Grammar, you felt that you should know something about girls. And we didn’t have very much contact with them. We met them during the holidays, obviously. I don’t remember having what these days seem to carry on, happen quite early in one teens. Sexual activity. I merely thought about it and hoped

27:30

for it and it never happened. A boys only boarding school…. Now of course, my old school has got girls. It was rather like the navy later on, I think. We had WRANS [Women’s Royal Australian Naval Service] in England and WRANS here and finally accepted, but never in any of my ships, did I actually have women serving under me. Now they have them as a matter of course, and the captains I speak to say, “Oh yes, no problems at all.”

28:00

I don’t really believe them.

Why is that?

Well, because of human nature being what it is, there must be problems. But they apparently deal with them all right. And I suppose it would be the same at co-ed boarding school these days. The masters and the headmasters would have problems to deal with, unless they accept it completely as a normal thing to let people carry on, but I don’t know that they would.

28:35

Did you feel that, given your history, of your family and the other men around you, did it feel that it was inevitable for you to be involved with the armed forces at some point?

Obviously the fact that I tried at the age of thirteen for the navy…. I had shown an interest in the navy.

29:00

I had hardly seen the sea, actually, but as I think I mentioned earlier on, I must have realised that if I had gone into the army I would have had a hard load to bear, because my father had done so well, people would tend to say, “Smyth can hardly keep up with his father’s reputation, can he?” So the navy, perhaps,

29:30

that was perhaps I went more for the navy. I liked the idea of it, and everything I had read about it. Inevitably, once I failed, I still wanted to try again. It was still peacetime then, of course. When the war came, there was no question about it. They had this special entry that they had just introduced to build up their numbers a little bit in the permanent navy. My father,

30:00

obviously, kept his ear to the ground and knew about it. There was no question. I thought it was a great idea to apply. Two or three other friends at school had gone in, just ahead of me. Ian Mackintosh, who died the other day. Tony Sennett, who also died the other day. They had gone into the navy. So even in peacetime, and even as war started, it was the obvious thing to do. Inevitability?

30:30

I would have had to do something in the war, there was no question in my mind about that. My brother and sister were over in England. They had gone over, just before the war. My brother had a scholarship at Cambridge; my sister went to be finished in France or something. They were both caught up in the war there. She joined the WAAF [Women’s Auxiliary Air Force], the air force. He joined the Welsh Guards because of my mother’s Welsh upbringing,

31:00

and he fought right through the war. So it sort of fitted in nicely, that we had the navy, army, air force amongst the three of us. So off we went to the war. My father had already had one heart attack by then. He was fairly old, he was seventy something by then. In those days, that was old. He became a bit of an armchair strategist, I think. I didn’t see much of him once I went away to the war. Within a year of my going

31:30

away he died of a second heart attack. And in a way, I think, just as well. He was too busy saying, “These young generals don’t know what they’re doing these days.” He was frustrated. He would have loved to have been there, but he was too old to do it. He was probably best off this Earth.

It must have been very difficult for him, not to be active…

Yes, I’m sure he wanted to,

32:00

but he had had, already, one heart attack. He’d been due to lead the Anzac March, for the first time, I think in about 1938, and just before it he had a heart attack, lifting a sheep over a fence. So he never did lead the march, which was always a great pity. I’ve led it twice, so I’ve made up for it.

Prior to the war

32:32

you said that you tried to get into the navy in ’36. Did you have any awareness, or what information did you have about what was going on in Europe?

Well, I think my father could see the war coming again. Not as early as that, perhaps, ‘36….

33:04

Germany, he distrusted. We had a German fraulein as one of our governesses, a bit earlier than that. I remember going through the family photograph album, years later…. There had been photographs of us sitting on the front steps, with the fraulein as part of the group,

33:32

and he had blackened out her face in all the photographs. I think that must have been when the war had actually started he might have done that. I don’t remember the time. He could see war coming. My wife’s father, similarly, they both… My wife’s father had come out after the war, too. They’d both been British.

34:00

He’d been in the Australian submarine, as the second in command. The two officers were British submarine officers. He came out after the war, and he similarly settled after he married an Australian girl, in that case. And my wife often talks of how he, in the years of the 1930s, he was lecturing at schools, he was talking over the ABC [Australian Broadcasting Corporation], and

34:30

warning Australia that war was coming again. He tried to get into the navy, but the Australian Navy said no, they didn’t want him. The day he was killed in a ridiculous accident, war had broken out a few days before. And that day he got a letter from the Royal Navy saying, “Yes, we are calling you up and we will appoint you to Singapore. Going to sea, you’re too old for that, so we’ll put you on the base staff there.”

35:01

So he, poor chap, having spent the First War as a prisoner of the Turks, would have found himself in the Second [World] War as a prisoner of the Japanese. But both our fathers were obviously well aware there was another war pending, in those years just before the war. That must have rubbed off on us.

Did you listen to the radio broadcasts with them, or something like that?

I can remember when the King

35:30

died, King George V. Now that must have been about 1935, ’36? We knew he was ill. My father was terribly fond of him, having known him. And we knew he was ill, and we all went out and we sat in our new motorcar, which had a radio. And that was the only radio that we had. We didn’t have one in the house. And we sat in it. And I can remember that night after my bedtime,

36:02

we heard that the King had died, and my father almost wept. “We’ve lost a great man,” and all that. He was very loyal and British and that sort of thing. So we didn’t listen to very many radios, obviously, if there was just the one in the car. Then as the war got closer, we obviously had a radio. And I can remember the night when we heard Menzies [Australian Prime Minister]

36:30

announcement that, “Of course, Australia is also at war.” We were all sort of…. oh, how long is this going to last? Are we going to be in it? That was ‘39, I was sixteen. A year later I was in it, and it lasted six years. Like the people I’ve been reading about from the First War , they were all so keen to get into the war, because they thought it would be over by Christmas, in 1914. And we rather wondered the same, in 1939.

37:00

But the bastard lasted six years.

Did you have the same excitement about it? Or were you more cautious?

Oh, I think I had been frightened…. cautious, yes. But there was no question in my mind that obviously if it lasted long enough that I would be in it to some extent, and the navy would be the obvious thing.

But you didn’t approach it with the same kind of spirit of adventure?

I don’t think so, no.

37:31

We had been fairly well brought up that wars were not always great fun.

Where did you find out that it was a bad thing?

38:00

Well, I think we had all read…. If we hadn’t been told a lot about the war, which we had, we’d also read a lot and war was not the adventurous thing that my father’s early days probably had been. So, he was horrified by the way that World War 1 went. The trench warfare and all that had obviously horrified him because

38:30

he had been happy prancing around the prairies on his horse, and charging and doing the things that, in those days, were probably great fun. If he wasn’t chasing people, he was chasing pigs in India. Pig-sticking and hog-hunting, or shooting elephants. It had been a great adventure, soldiering, in his early days. And World War 1 changed all that, for a lot of people. So I don’t think we looked at it with great adventure. But it was

39:00

still adventurous, yes. If there was a war on, we wanted to be in it. And we didn’t worry, right through the war, really, if we were going to be killed the next day. We didn’t have wives back home, we were only youngsters. Somehow we knew we’d survive, a charmed life. I was lucky, I was shot [at], I was never wounded, hardly. It was much better than it could have been. And that might have been influencing me, too,

39:30

into going into the navy. I didn’t like the idea of trench warfare from what I’d heard of it, or any army warfare for that matter.

So you must have been influenced by details of the First World War. Particularly of the Infantry….

I think so, yes. It was all Infantry by the end, except people that went into tanks.

40:00

The cavalry had virtually…. Well, in the Middle East war, they were still doing charges of cavalry. The Light Horse of Beersheeba and everything. I didn’t mention that just before I went into the navy, I joined the Light Horse. The local Militia at Balmoral was the Light Horse. I applied for the navy, and

40:30

virtually expected to go into the navy, but they were still waiting to accept me, so I joined the Light Horse. I think I was in for fully three weeks, but it’s been rather nice to tell the army since that I was once in the cavalry, or the Light Horse. And the Light Horse, of course, is quite a nostalgic sort of memory for a lot of soldiers, who didn’t know it when it existed, as it did then.

41:00

Even in the First War , the Light Horse went over with their horses, but they never really fought. Gallipoli, at that awful battle at the Neck, was Light Horse, but they were behaving as Infantry. Light Horse were not true Cavalry Mounted Infantry, that was another description for them.

We better pause there.

Part 3/11

00:35

So now I wanted to ask you about the first time you applied for the navy. Can you tell us what happened? What the process was?

I think there were about four hundred applicants throughout Australia for this twelve, thirteen year old entry, for which they needed about fifteen. War clouds were not yet threatening too much,

01:01

and they were only taking in about fifteen cadet midshipmen, as they called them, each year. We first of all had to do an exam. I think I did that in Geelong. I might have had to come to Melbourne for it. There were two or three others with me, including David Hamer, who was the younger brother of Dick Hamer [Premier of Victoria, Deputy Premier, Chief Secretary and Minister], the former premier. He was somebody I knew quite well at school. We then

01:30

had to do a medical and then an interview. I didn’t get the interview, because at the medical, which I think was conducted by a very naval looking doctor, in a naval uniform anyhow, and he stripped me naked and started at the top and worked down. And everything seemed to be all right until he got to my feet. And I remember him saying to somebody, “I think this young gentleman has very flat feet.”

02:00

And I wasn’t brave enough…. I think I might have touched on this earlier in the talk to say, “But I’ve got very strong feet. They’ve just taken up the shape of the land on which they walked because I didn’t put shoes on until I came to see you today, sir.” But I wasn’t brave enough to say that. They were obviously looking for any excuse to cut that four or five hundred down to fifteen. So I failed miserably and was told that I wasn’t acceptable.

02:30

David Hamer actually did get into the navy then, and went through the whole four years of academic training. I was rather put off at the time. My father was very cross, because he thought his son should have been accepted into the navy. I suspect he rang people afterwards, but he couldn’t do anything about it. But we did then settle down, while I was at school. I was given special exercises

03:00

to strengthen my feet. Which I didn’t think really needed any strengthening. But anyway, I waved my ankles around quite a lot. When the time came again, going ahead, four years later, they didn’t even look at my feet. There was a war on and I was in. But that was the process. There were fifteen who got in, one of them was, as I say, my schoolmate David Hamer, who I have known ever since. He died only last year actually.

03:31

All right, tell us about the process the second time you went around?

Much the same, I think. I remember I’d got my matriculation at the end of 1939, my leaving exams, and matriculated. So for the next six months at school, in 1940, I had a lovely time working by myself in the library, getting ready for the exam for the navy. Which I didn’t really do very much work

04:00

for. I think I had a lovely time reading up all the books that I had always wanted to read. Studying heraldry amongst other things, I seem to remember. At any rate, the exam finally came. Two other people from Geelong Grammar sat for the navy with me. We all got through the initial exam. It was the same process, except that we were four years older. The medical exam I got through. As I say, they hardly looked at my feet.

04:30

and they were looking for…. Only a few, but I think the number they finally took in our entry was only seven. Then the interview. The interview I do remember. Not having done the interview the first time, in 1936. It had all the typical questions. “Do you remember the number of the bus you came to the interview in?” No, sir, I came in the tram.” “What number was it?” “One, two,

05:00

three, four.” “Was it really?” “Yes, sir.” Because you had been told you had to invent something quickly to give an answer. I do remember they said, “Oh your father…” And they asked about my father and I proudly said, “Yes, he got a Victoria Cross.” And they said, “Ahh, what colour is the ribbon of the Victoria Cross?” Well, I had been seeing it all my life…. You saw it just a little while ago. What colour would you call it? I said, “It’s a sort of a deep purple.” And they said, “No,

05:30

no, no. It’s crimson.” And I said, “No, that doesn’t sound right to me. It’s a deep purple to me.” And I think that almost lost me my chance of getting in. But that is the only thing I can really remember they asked me. Then we had to wait a couple of weeks, then finally I got a letter saying “Yes, you are being appointed as a cadet midshipman, etc.” And I rushed around to the other chap, Haslop, his name was, I remember now. I said, “Have you had your letter?”

06:00

And he said, “No.” And two days later I left school and he still hadn’t got a letter, then he rang up another friend and said, “I’ve got a letter saying no, I’ve missed it.” He joined the air force and was killed.

Were you given any encouragement or coercion from the school?

My headmaster was the famous doctor, later Sir, James Darling.

06:30

He was headmaster for 30 years, in 1930. And he had actually been over in England at the beginning of the war. He had been in the First War in the British Army. He got rushed back, and I remember my farewell…. We were all encouraged, obviously. I think the percentage from Geelong Grammar who joined the services was something like 95%. There was

07:00

no question that you joined and you fought for your country. I do remember when he was saying his final farewells to me, he said, “Well, great. I’m glad you’re in the navy. But at least you might have joined a decent navy like the Royal Navy, instead of the Australian Navy.” He had just sent Ian Mackintosh and David Shore and a few others, David Spooner, over to the Royal Navy, and he was obviously felt that was the proper navy to join.

07:30

Ian Mackintosh finished up as Vice-Admiral Sir Ian Mackintosh, and he died only a few months ago and we’ve got a memorial service for him, at the school, next month. So that would have probably influenced Dr Darling a little bit when he said that. But I felt a bit cross about that. He should have said, “Congratulations. You’ve joined the best navy in the world.” But no, he said, “You should have joined a decent navy.”

Was that an option for you, to join the Royal Navy?

I think once the same idea had

08:00

had been into our navy, that the other one no longer existed. They had joined, I think, probably three years ahead of me. And that was the only way, at that age, that you could get into a navy. As soon as the Australian Navy introduced, it, and for instance Tony Sennett, who finished up as the head of the War Fleet Services, a few years ago, he was the first of the Australians to join the Australian Navy, especially.

08:30

In fact, he went to England for his training, the same as the others had done, but he was in the Australian Navy. Chick Murray, who was the governor of Victoria a few years ago, Admiral Murray, he was also in that lot, the first lot. We were the third or fourth lot. In fact, we always say that when they saw us, they gave the scheme away. We were the last lot. They only took seven in our entry. There were three seamen officers,

09:00

Executive as we used to be called, and four engineers. So I was one of only three to be accepted then, out of I don’t know how many applicants. It was just a small building up of the permanent navy to replace what they felt they would lose in the war. It was probably about right when you work it out afterwards. Our group, the David Hamer group and all that, probably lost about seven out of their

09:30

fifteen or twenty. So we were the replacements that the navy had put in, in advance. Somebody did their sums well.

Do you remember any posters or newsreels or songs of the time encouraging people to join up?

10:00

No, I don’t. There must have been. The old First World War image of Kitchener [Lord Kitchener. Horatio Herbert Kitchener] pointing at you saying, “Your Country Needs You.” There must have been things like that. I don’t remember any, there probably were. I know there was an enormous enthusiasm for people to join. Whether the people themselves were that keen…. But again, at home

10:30

I remember…. I got leave on and off, and the locals were gradually going off to war. Whether there were sort of recruiting campaigns, whether the sergeant majors came around to the country saying, “We want you to join.” I don’t know. I was too busy away, trying to be a sailor.

What was your parents reaction then, when you joined up?

11:01

Oh, they were delighted, obviously, that I had finally made it. No doubt there were all sorts of qualms in their minds. But, at the same time, as I say my brother and my sister had both joined, over in England, which was far close to the war, in those days. Long before the Japs came in. But I don’t remember anything except pride that their three

11:30

kids were serving. And my father was very proud obviously. I think I saw him once on leave, then I went away. I remember I was in Aden. A signal came through. It wasn’t for Midshipman Smyth, it was for Midshipman Sloane. And there were was no midshipman called Sloane, and the signal said, “Your father has had a

12:00

heart attack and that he is gravely ill.” And they got all the midshipmen in and said, “Which of you do you think this is?” And I said, “I think it might be me.” I said, “Let’s have a look at that name…. “ And I jotted down the Morse [Code] for Smyth, which is dot-dot-dot-dash-dash-dah-de-dah-dah-dah-de-de-de-dit” And then I jotted down the same for Sloane.

12:30

And they were so similar that somehow in the transmission it had come out as Sloane instead of Smyth, and I said, “I think this is for me.” And sure enough the next day there was a signal, for Smyth this time, saying that, “Your father has now died.” The funny things that you remember. Nobody else had thought to work out the Morse Code.

Not a great way to find out….

No.

13:00

Tell me then, about your first experiences once you were actually inducted into the navy?

Right, straight down to Flinders Naval Depot, as it was then called, HMAS Cerberus…. Well, it was Cerberus then, too, but it’s main name was Flinders Naval Depot. We were met in Melbourne by one of our own age group who was a cadet captain in the senior year. Guy Griffiths,

13:30

who’s still around. I’ve known him all my life, since then. He took us down in a bus, all seven of us. And we were there about three days ahead of the normal returning…. It was like a school, them being away for September holidays, I suppose. It was September, 1940, then, and we had about three days in getting our uniform, and learning to double everywhere in formation.

14:01

And being told by him and the term officer, who was a Reserve officer, who had been in permanent navy way back, and had gone out and become a chemist, I think. I can’t remember his name. But he was our sort of term officer. And Guy Griffiths was telling us all about being a cadet midshipman and how we behaved. And then of course the main group came back and eyed us over

14:30

and tried to treat us like first year. First year, you’d get a pretty fair time. Not quite as bad as the army has tended to do, over the years, when you’ve heard about bastardisation and things. But they were doing initiations and things, for the first year. And the senior year got us and said, “Now, you are going to be initiated.” And we all said, “Wait a minute…” And one of our chaps had been at university for a year or two. I think he was

15:00

twenty one. I was only seventeen. I was the youngest of the group. And he said, “Now, wait a minute. I think I’m older than you. I think I’m bigger than you, if you try anything like that…” They hadn’t quite figured out that we were more of a senior group of new entries than the poor little thirteen year olds who would join each year in January. So we avoided all that. We were embraced almost,

15:30

although suspiciously. They never really liked it. Even now, those thirteen-year-old entries look on us as, “You were the specials. You didn’t go through the four years that we did.” We on the other hand, as I say, got out of any initiation. And we didn’t do any academic work, really. I think we had a Naval History and Trigonometry. Spherical trigonometry, because you

16:00

needed that for navigation work. But mainly we were doing gunnery and torpedoes and physical training. All the sort of naval things, the naval drill, whereas they were still being treated as schoolboys, really. So we only did two terms. We did September to December, and then the January to March. Then we went off to sea, about March, 1941.

16:30

Our age group graduated, then we took part in the graduation parade at the end of 1940. They went off to sea ahead of us. Then to rub salt into their annoyance, later on, because we had had this twenty one year old, and a couple of nineteens, the navy worked out that we were older. So they gave us an extra six months seniority,

17:01

and we all finished up senior to the ones who had done their four years training and that again, they never quite forgave us. Right through the navy…. .Guy Griffiths actually, I think he got promoted to captain just ahead of him. But he made admiral and I didn’t. So at any rate, it was a very pleasant time. I was used to all the…. .I had a been a sergeant major in the school cadet corps, so I knew about drill,

17:30

although the naval drill was a bit different. I knew how to be boarder at school, for many years. There was no homesickness or anything like that, it was just excitement to actually be in the navy and doing proper navy things, and looking forward to getting away to sea, which we did. Pretty quickly.

Tell us about your initial training , then. What sort of things did you learn?

Well, gunnery

18:00

and lots of actual learning the theory of gunnery, then doing gun drill on the six inch and four inch guns they had there. Lifting a six-inch projectile is pretty heavy. One poor chap dropped one on his toe. He was in hospital for a little while. I did finish up in hospital at one stage. I got a sort of boil on my foot, if I remember it was, and they had to put me in hospital, because I

18:30

had fainted on parade but I had refused to actually fall over. I suddenly realised everything was going around and around and I turned right and I marched off the parade and collapsed on the corner of the drill hall, and was taken to hospital. But at least I hadn’t fallen flat on my face, so I felt rather proud of that. We went through all the usual boat drill. Pulling whalers…. pulling being the word ‘rowing’ in the navy. Cutters and whalers.

19:00

Sailing, learning to sail. I had never learned anything like that. So all the very naval things plus, as I say, talks on history, talks on seamanship, which covers nearly everything you might find on the ship to do. All the ropes and rigging of an old ship, and the rigging and equipment of a new ship. How you handle a ship. How you handle boats. We learned not only the pulling and sailing, but also the motor

19:30

boats they had down there. Because as soon as you got to sea, as a midshipman, you find yourself, virtually on your first command, you were given command of one of the ship’s boats. That was your boat and you had your crew and they had to keep smart and clean, and you had to drive it, and you had to drive it so that you didn’t crash into things when you had admirals and captains on board. So it was all a whole new experience for a country boy, really, but somehow it seemed all right and proper. And we knew we were going off

20:00